Arabic literature ( ar, الأدب العربي /

ALA-LC

ALA-LC (American Library AssociationLibrary of Congress) is a set of standards for romanization, the representation of text in other writing systems using the Latin script.

Applications

The system is used to represent bibliographic information by ...

: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as

prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the f ...

and

poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

, produced by writers in the

Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

. The Arabic word used for literature is ''

Adab'', which is derived from a meaning of

etiquette

Etiquette () is the set of norms of personal behaviour in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviours that accord with the conventions and norms observed and practised by a ...

, and which implies politeness, culture and enrichment.

Arabic literature emerged in the 5th century with only fragments of the written language appearing before then. The

Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

, widely regarded as the finest piece of literature in the

Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, would have the greatest lasting effect on

Arab culture

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arab ...

and its literature. Arabic literature flourished during the

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, but has remained vibrant to the present day, with poets and prose-writers across the

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

, as well as in the

Arab diaspora

Arab diaspora (also known as MENA diaspora, as a short version for the Middle East and North Africa diaspora) refers to descendants of the Arab people, Arab Emigration, emigrants who, voluntarily or as refugees, emigrated from their native lands ...

, achieving increasing success.

History

''Jahili''

is the literature of the pre-Islamic period referred to as

''al-Jahiliyyah'', or "the time of ignorance".

In pre-Islamic Arabia, markets such as

Souq Okaz, in addition to and , were destinations for caravans from throughout the peninsula.

At these markets poetry was recited, and the dialect of the

Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qur ...

, the tribe in control of Souq Okaz of Mecca, became predominant.

Poetry

Notable poets of the pre-Islamic period were

Abu Layla al-Muhalhel and

Al-Shanfara Al-Shanfarā ( ar, الشنفرى; died c. 525 CE) was a semi-legendary pre-Islamic poet tentatively associated with Ṭāif, and the supposed author of the celebrated poem '' Lāmiyyāt ‘al-Arab''. He enjoys a status as a figure of an archetypa ...

.

There were also the poets of the ''

Mu'allaqat

The Muʻallaqāt ( ar, المعلقات, ) is a group of seven long Arabic poems. The name means The Suspended Odes or The Hanging Poems, the traditional explanation being that these poems were hung in the Kaaba in Mecca, while scholars have also ...

'', or "the suspended ones", a group of poems said to have been on display in

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

.

These poets are

Imru' al-Qais

Imruʾ al-Qais Junduh bin Hujr al-Kindi ( ar, ٱمْرُؤ ٱلْقَيْس جُنْدُح ٱبْن حُجْر ٱلْكِنْدِيّ, ALA-LC: ''ʾImruʾ al-Qays Junduḥ ibn Ḥujr al-Kindīy'') was an Arab king and poet in the 6th century, an ...

,

Tarafah ibn al-‘Abd, ,

Harith ibn Hilliza Al-Ḥārith ibn Ḥilliza al-Yashkurī ( ar, الحارث بن حلزة اليشكري) was a pre-Islamic Arabian poet of the tribe of Bakr, from the 5th century. He was the author of one of the seven famous pre-Islamic poems known as the ''Mu'all ...

,

Amr ibn Kulthum

ʿAmr ibn Kulthūm ibn Mālik ibn ʿAttāb ʾAbū Al-ʾAswad al-Taghlibi ( ar, عمرو بن كلثوم; 526–584) was a poet and chieftain of the Taghlib tribe in pre-Islamic Arabia. One of his poems was included in the ''Mu'allaqat''. He is t ...

,

Zuhayr ibn Abi Sulma

Zuhayr bin Abī Sulmā ( ar, زهير بن أبي سلمى; ), also romanized as Zuhair or Zoheir, was a pre-Islamic Arabian poet who lived in the 6th & 7th centuries AD. He is considered one of the greatest writers of Arabic poetry in pre-I ...

,

Al-Nabigha al-Dhubiyānī,

Antara Ibn Shaddad

Antarah ibn Shaddad al-Absi ( ar, عنترة بن شداد العبسي, ''ʿAntarah ibn Shaddād al-ʿAbsī''; AD 525–608), also known as ʿAntar, was a pre-Islamic Arab knight and poet, famous for both his poetry and his adventurous life ...

,

al-A'sha al-Akbar, and

Labīd ibn Rabī'ah.

Al-Khansa

Tumāḍir bint ʿAmr ibn al-Ḥārith ibn al-Sharīd al-Sulamīyah ( ar, تماضر بنت عمرو بن الحارث بن الشريد السُلمية), usually simply referred to as al-Khansāʾ ( ar, الخنساء, links=no, meaning "snub-n ...

stood out in her poetry of ''

rithā'

Rithā’ ( ar, رثاء) is a genre of Arabic poetry corresponding to elegy or lament. Along with elegy proper (''marthiyah'', plural ''marāthī''), ''rithā’'' may also contain ''taḥrīḍ'' (incitement to vengeance).

Characteristics

The ...

'' or

elegy

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

.

was prominent for his ''

madīh'', or "

panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

", as well as his , or "

invective

Invective (from Middle English ''invectif'', or Old French and Late Latin ''invectus'') is abusive, reproachful, or venomous language used to express blame or censure; or, a form of rude expression or discourse intended to offend or hurt; vituperat ...

".

Prose

As the literature of the Jahili period was transmitted orally and not written, prose represents little of what has been passed down.

The main forms were parables ( ''al-mathal''), speeches ( ''al-khitāba''), and stories ( ''al-qisas'').

was a notable Arab ruler, writer, and

orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14th ...

.

was also one of the most famous rulers of the Arabs, as well as one of their most renowned speech-givers.

The Qur'an

The

Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

, the main

holy book

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

of

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, had a significant influence on the Arabic language, and marked the beginning of

Islamic literature

Islamic literature is literature written by Muslim people, influenced by an Islamic cultural perspective, or literature that portrays Islam. It can be written in any language and portray any country or region. It includes many literary forms in ...

. Muslims believe it was transcribed in the Arabic dialect of the

Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qur ...

, the tribe of

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

.

As Islam spread, the Quran had the effect of unifying and standardizing Arabic.

Not only is the Qur'an the first work of any significant length written in the language, but it also has a far more complicated structure than the earlier literary works with its 114 ''

suwar

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

'' (chapters) which contain 6,236 ''

ayat'' (verses). It contains

injunction

An injunction is a legal and equitable remedy in the form of a special court order that compels a party to do or refrain from specific acts. ("The court of appeals ... has exclusive jurisdiction to enjoin, set aside, suspend (in whole or in pa ...

s,

narrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether nonfictional (memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travel literature, travelogue, etc.) or fictional (fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller (ge ...

s,

homilies

A homily (from Greek ὁμιλία, ''homilía'') is a commentary that follows a reading of scripture, giving the "public explanation of a sacred doctrine" or text. The works of Origen and John Chrysostom (known as Paschal Homily) are considered ex ...

,

parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, w ...

s, direct addresses from God, instructions and even comments on how the Qu'ran will be received and understood. It is also admired for its layers of metaphor as well as its clarity, a feature which is mentioned in

An-Nahl

The Bee (Arabic: الْنَّحْل; ''an-nahl'') is the 16th chapter (''sūrah'') of the Qur'an, with 128 verses ('' āyāt''). It is named after honey bees mentioned in verse 68, and contains a comparison of the industry and adaptability of h ...

, the 16th surah.

The 92

Meccan suras, believed to have been revealed to Muhammad in Mecca before the

Hijra

Hijra, Hijrah, Hegira, Hejira, Hijrat or Hijri may refer to:

Islam

* Hijrah (often written as ''Hejira'' in older texts), the migration of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE

* Migration to Abyssinia or First Hegira, of Muhammad's followers ...

, deal primarily with , or "the principles of religion", whereas the 22

Medinan suras, believed to have been revealed to him after the Hijra, deal primarily with

Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

and prescriptions of Islamic life.

The word ''qur'an'' comes from the Arabic root qaraʼa (قرأ), meaning "he read" or "he recited"; in early times the text was transmitted orally. The various tablets and scraps on which its suras were written were compiled under

Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honor ...

(573-634), and first transcribed in unified ''masahif'', or copies of the Qur'an, under

Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic proph ...

(576-656).

Although it contains elements of both prose and poetry, and therefore is closest to ''

Saj'' or

rhymed prose Rhymed prose is a literary form and literary genre, written in unmetrical rhymes. This form has been known in many different cultures. In some cases the rhymed prose is a distinctive, well-defined style of writing. In modern literary traditions ...

, the Qur'an is regarded as entirely apart from these classifications. The text is believed to be

divine revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

and is seen by

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

as being eternal or 'uncreated'. This leads to the doctrine of ''

i'jaz

In Islam, ''’i‘jāz'' ( ar, اَلْإِعْجَازُ, al-’i‘jāz) or inimitability of the Qur’ān is the doctrine which holds that the Qur’ān has a miraculous quality, both in content and in form, that no human speech can match. ...

'' or inimitability of the Qur'an which implies that nobody can copy the work's style.

This doctrine of ''i'jaz'' possibly had a slight limiting effect on Arabic literature; proscribing exactly what could be written. Whilst Islam allows Muslims to write, read and recite poetry, the Qur'an states in the 26th sura (

Ash-Shu'ara

Ash-Shu‘ara’ ( ar, الشعراء, ; The Poets) is the 26th chapter (sūrah) of the Qurʾan with 227 verses ( āyāt). Many of these verses are very short. The chapter is named from the worAsh-Shu'arain ayat 224.

The chapter talks about v ...

or The Poets) that poetry which is blasphemous, obscene, praiseworthy of sinful acts, or attempts to challenge the Qu'ran's content and form, is forbidden for Muslims.

This may have exerted dominance over the pre-Islamic poets of the 6th century whose popularity may have vied with the Qur'an amongst the people. There was a marked lack of significant poets until the 8th century. One notable exception was

Hassan ibn Thabit

Ḥassān ibn Thābit ( ar, حسان بن ثابت) (born c. 563, Medina died 674) was an Arabian poet and one of the Sahaba, or companions of Muhammad, hence he was best known for his poems in defense of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

He was b ...

who wrote poems in praise of

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

and was known as the "prophet's poet". Just as the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

has held an important place in the literature of other languages, The Qur'an is important to Arabic. It is the source of many ideas, allusions and quotes and its moral message informs many works.

Aside from the Qur'an the ''

hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

'' or tradition of what Muhammed is supposed to have said and done are important literature. The entire body of these acts and words are called ''

sunnah

In Islam, , also spelled ( ar, سنة), are the traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time evidently saw and followed and passed ...

'' or way and the ones regarded as ''sahih'' or genuine of them are collected into hadith. Some of the most significant collections of hadith include those by

Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj

Abū al-Ḥusayn ‘Asākir ad-Dīn Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj ibn Muslim ibn Ward ibn Kawshādh al-Qushayrī an-Naysābūrī ( ar, أبو الحسين عساكر الدين مسلم بن الحجاج بن مسلم بن وَرْد بن كوشاذ ...

and

Muhammad ibn Isma'il al-Bukhari.

The other important genre of work in Qur'anic study is the ''

tafsir

Tafsir ( ar, تفسير, tafsīr ) refers to exegesis, usually of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' ( ar, مُفسّر; plural: ar, مفسّرون, mufassirūn). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, in ...

'' or

commentaries Arab writings relating to religion also includes many

sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

s and devotional pieces as well as the sayings of

Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

which were collected in the 10th century as ''

Nahj al-Balaghah'' or ''The Peak of Eloquence''.

Rashidi

Under the

Rashidun

, image = تخطيط كلمة الخلفاء الراشدون.png

, caption = Calligraphic representation of Rashidun Caliphs

, birth_place = Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia present-day Saudi Arabia

, known_for = Companions of t ...

, or the "rightly guided caliphs," literary centers developed in the

Hijaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provinc ...

, in cities such as

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

and

Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

; in the Levant, in

Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

; and in Iraq, in

Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf ...

and

Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

.

Literary production—and poetry in particular—in this period served the spread of Islam.

There was also poetry to praise brave warriors, to inspire soldiers in ''

jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

'', and

''rithā''' to mourn those who fell in battle.

Notable poets of this rite include

Ka'b ibn Zuhayr

Kaʿb ibn Zuhayr ( ar, كعب بن زهير) was an Arabian poet of the 7th century, and a contemporary of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Ka'b ibn Zuhayr was the writer of ''Bānat Suʿād (Su'ād Has Departed)'', a qasida in praise of Muhammad. ...

,

Hasan ibn Thabit, , and

Nābigha al-Ja‘dī.

There was also poetry for entertainment often in the form of ''

ghazal

The ''ghazal'' ( ar, غَزَل, bn, গজল, Hindi-Urdu: /, fa, غزل, az, qəzəl, tr, gazel, tm, gazal, uz, gʻazal, gu, ગઝલ) is a form of amatory poem or ode, originating in Arabic poetry. A ghazal may be understood as a ...

''.

Notables of this movement were

Jamil ibn Ma'mar,

Layla al-Akhyaliyya

Layla bint Abullah ibn Shaddad ibn Ka’b al-Akhyaliyyah () (d. c. AH 75/694×90/709 CE), or simply Layla al-Akhyaliyyah () was a famous Umayyad Arab poet who was renowned for her poetry, eloquence, strong personality, and beauty. Nearly fifty of h ...

, and

Umar Ibn Abi Rabi'ah.

Ummayad

The

First Fitna

The First Fitna ( ar, فتنة مقتل عثمان, fitnat maqtal ʻUthmān, strife/sedition of the killing of Uthman) was the first civil war in the Islamic community. It led to the overthrow of the Rashidun Caliphate and the establishment of ...

, which created the

Shia–Sunni split over the rightful

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, had a great impact on Arabic literature.

Whereas Arabic literature—along with Arab society—was greatly centralized in the time of

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

and the

Rashidun

, image = تخطيط كلمة الخلفاء الراشدون.png

, caption = Calligraphic representation of Rashidun Caliphs

, birth_place = Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia present-day Saudi Arabia

, known_for = Companions of t ...

, it became fractured at the beginning of the period of the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

, as power struggles led to tribalism.

Arabic literature at this time reverted to its state in

''al-Jahiliyyah'', with markets such as

Kinasa near

Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf ...

and near

Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

, where poetry in praise and admonishment of political parties and tribes was recited.

Poets and scholars found support and patronage under the Umayyads, but the literature of this period was limited in that it served the interests of parties and individuals, and as such was not a free art form.

Notable writers of this political poetry include

Al-Akhtal al-Taghlibi,

Jarir ibn Atiyah

Jarir ibn Atiyah al-Khatfi Al-Tamimi ( ar, جرير بن عطية الخطفي التميمي) () was an Arab poet and satirist. He was born in the reign of Najd Arabia, and was a member of the tribe Kulaib, a part of the Banu Tamim. He was a nat ...

,

Al-Farazdaq

Hammam ibn Ghalib ( ar, همام بن غالب; born c. 641; died 728–730), most commonly known as Al-Farazdaq () or Abu Firas, was an Arab poet.

He was born in, Kazma. He was a member of Darim, one of the most respected divisions of the Bani T ...

,

Al-Kumayt ibn Zayd al-Asadi, , and .

There were also poetic forms of

''rajaz''—mastered by and —and ''ar-Rā'uwīyyāt,'' or "

pastoral poetry

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

"—mastered by and

Dhu ar-Rumma.

Abbasid

The

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

period is generally recognized as the beginning of the

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, and was a time of significant literary production. The

House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, بيت الحكمة, Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

in

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

hosted numerous scholars and writers such as

Al-Jahiz

Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو عثمان عمرو بن بحر الكناني البصري), commonly known as al-Jāḥiẓ ( ar, links=no, الجاحظ, ''The Bug Eyed'', born 776 – died December 868/Jan ...

and

Omar Khayyam

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Abū al-Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm Nīsābūrī (18 May 1048 – 4 December 1131), commonly known as Omar Khayyam ( fa, عمر خیّام), was a polymath, known for his contributions to mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, an ...

. A number of stories in the ''

One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'' feature the Abbasid caliph

Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

.

Al-Hariri of Basra

Abū Muhammad al-Qāsim ibn Alī ibn Muhammad ibn Uthmān al-Harīrī ( ar, أبو محمد القاسم بن علي بن محمد بن عثمان الحريري), popularly known as al-Hariri of Basra (1054 – 10 September 1122) was an Arab po ...

was a notable literary figure of this period.

Some of the important poets in were:

Bashar ibn Burd

Bashār ibn Burd ( ar, بشار بن برد; 714–783), nicknamed al-Mura'ath, meaning "the wattled", was a Persian poet of the late Umayyad and early Abbasid periods who wrote in Arabic. Bashar was of Persian ethnicity; his grandfather was taken ...

,

Abu Nuwas

Abū Nuwās al-Ḥasan ibn Hānī al-Ḥakamī (variant: Al-Ḥasan ibn Hānī 'Abd al-Awal al-Ṣabāḥ, Abū 'Alī (), known as Abū Nuwās al-Salamī () or just Abū Nuwās Garzanti ( ''Abū Nuwās''); 756814) was a classical Arabic poet, ...

,

Abu-l-'Atahiya

Abū al-ʻAtāhiyya ( ar, أبو العتاهية; 748–828), full name Abu Ishaq Isma'il ibn al-Qasim ibn Suwayd Al-Anzi (), was among the principal Arabic, Arab poets of the early Islamic era, a prolific ''muwallad'' Arabic poetry, poet of asc ...

,

Muslim ibn al-Walid,

Abbas Ibn al-Ahnaf

Abu al-Fadl Abbas Ibn al-Ahnaf () (750 in Basra-809), was an Arab Abbasid poet from the tribe of Banu Hanifa. His work consists solely of love poems ( ghazal). It is "primarily concerned with the hopelessness of love, and the personae in his compo ...

, and .

Andalusi

Andalusi literature

Andalusi literature was produced in

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

, or Islamic Iberia, from its

Muslim conquest

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He esta ...

in 711 to either the

Catholic conquest of Granada in 1492 or the

Expulsion of the Moors ending in 1614.

Ibn Abd Rabbih's ''

Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd

''al-ʿIqd al-Farīd'' (''The Unique Necklace'', ar, العقد الفريد) is an anthology attempting to encompass 'all that a well-informed person had to know in order to pass in society as a cultured and refined individual' (or '' adab''), c ...

'' (The Unique Necklace) and

Ibn Tufail's ''

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

''Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān'' () is an Arabic philosophical novel and an allegorical tale written by Ibn Tufail (c. 1105 – 1185) in the early 12th century in Al-Andalus. Names by which the book is also known include the ('The Self-Taught Philosop ...

'' were influential works of literature from this tradition. Notable literary figures of this period include

Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

,

Ziryab

Abu l-Hasan 'Ali Ibn Nafi, better known as Ziryab, Zeryab, or Zaryab ( 789– 857) ( ar, أبو الحسن علي ابن نافع, زریاب, rtl=yes) ( fa, زَریاب ''Zaryāb''), was a singer, oud and lute player, composer, poet, and teache ...

,

Ibn Zaydun

Abū al-Walīd Aḥmad Ibn Zaydūni al-Makhzūmī () (1003–1071) or simply known as Ibn Zaydun () or Abenzaidun was an Arab Andalusian poet of Cordoba and Seville. He was considered the greatest neoclassical poet of al-Andalus.

He reinvigorate ...

,

Wallada bint al-Mustakfi

Wallada bint al-Mustakfi ( ar, ولادة بنت المستكفي) (born in Córdoba in 994 or 1010 – died March 26, 1091) was an Andalusian poet.

Early life

Wallada was the daughter of Muhammad III of Córdoba, one of the last Umayyad Co ...

,

Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad,

Ibn Bajja

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

,

Al-Bakri

Abū ʿUbayd ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad ibn Ayyūb ibn ʿAmr al-Bakrī ( ar, أبو عبيد عبد الله بن عبد العزيز بن محمد بن أيوب بن عمرو البكري), or simply al-Bakrī (c. 1040–1 ...

,

Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, ...

,

Hafsa bint al-Hajj al-Rukuniyya,

Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theolo ...

,

Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , 'Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influenti ...

,

Ibn Quzman

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Isa Abd al-Malik ibn Isa ibn Quzman al-Zuhri ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن عيسى بن عبدالملك بن عيسى بن قزمان الزهري; 1087–1160) was the single most famous poet in the history of Al-Andalu ...

,

Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi

Abu Muhammad Salih b. Abi Sharif ar-Rundi () (or Abu-l-Tayyib/ Abu-l-Baqa Salih b. Sharif al-Rundi) was a poet, writer, and literary critic from al-Andalus who wrote in Arabic. His fame is based on his '' nuniyya'' entitled "" ''Rithaa' ul-Andalus' ...

, and

Ibn al-Khatib

Lisan ad-Din Ibn al-Khatib ( ar, لسان الدين ابن الخطيب, Lisān ad-Dīn Ibn al-Khaṭīb) (Born 16 November 1313, Loja– died 1374, Fes; full name in ar, محمد بن عبد الله بن سعيد بن عبد الله بن � ...

. The ''

muwashshah

''Muwashshah'' ( ar, موشح ' literally means "girdled" in Classical Arabic; plural ' or ' ) is the name for both an Arabic poetic form and a secular musical genre. The poetic form consists of a multi-lined strophic verse poem written ...

'' and ''

zajal

Zajal () is a traditional form of oral strophic poetry declaimed in a colloquial dialect. While there is little evidence of the exact origins of the zajal, the earliest recorded zajal poet was the poet Ibn Quzman of al-Andalus who lived from 1078 ...

'' were important literary forms in al-Andalus.

The rise of Arabic literature in al-Andalus occurred in dialogue with the

golden age of Jewish culture in Iberia. Most Jewish writers in al-Andalus—while incorporating elements such as rhyme, meter, and themes of classical Arabic poetry—created poetry in Hebrew, but

Samuel ibn Naghrillah

Samuel ibn Naghrillah (, ''Sh'muel HaLevi ben Yosef HaNagid''; ''ʾAbū ʾIsḥāq ʾIsmāʿīl bin an-Naghrīlah''), also known as Samuel HaNagid (, ''Shmuel HaNagid'', lit. ''Samuel the Prince'') and Isma’il ibn Naghrilla (born 993; died 1056 ...

,

Joseph ibn Naghrela

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, and

Ibn Sahl al-Isra'ili wrote poetry in Arabic.

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

wrote his landmark ''Dalãlat al-Hā'irīn'' (''

The Guide for the Perplexed

''The Guide for the Perplexed'' ( ar, دلالة الحائرين, Dalālat al-ḥā'irīn, ; he, מורה נבוכים, Moreh Nevukhim) is a work of Jewish theology by Maimonides. It seeks to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinical Jewish the ...

'') in Arabic using the

Hebrew alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet ( he, wikt:אלפבית, אָלֶף־בֵּית עִבְרִי, ), known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew languag ...

.

Maghrebi

Fatima al-Fihri

Fatima bint Muhammad al-Fihri al-Quraysh ( ar, فاطمة بنت محمد الفهري القرشية) was an Arab woman who is credited with founding the al-Qarawiyyin mosque in 857–859 AD in Fez, Morocco. She is also known as "Umm al-Banay ...

founded

al-Qarawiyiin University in

Fes

Fez or Fes (; ar, فاس, fās; zgh, ⴼⵉⵣⴰⵣ, fizaz; french: Fès) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco, with a population of 1.11 mi ...

in 859, recognised as the first university in the world. Particularly from the beginning of the 12th century, with sponsorship from the

Almoravid dynasty

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

, the university played an important role in the development of literature in the region, welcoming scholars and writers from throughout the Maghreb, al-Andalus, and the

Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

.

Among the scholars who studied and taught there were

Ibn Khaldoun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

,

al-Bitruji

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji () (also spelled Nur al-Din Ibn Ishaq al-Betrugi and Abu Ishâk ibn al-Bitrogi) (known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius) (died c. 1204) was an Iberian-Arab astronomer and a Qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī ...

,

Ibn Hirzihim (

Sidi Harazim

''For the teacher of Ash-Shadhili see Abu Abdallah ibn Harzihim''

Sidi Ali ibn Harzihim () or Abul Hasan Ali ibn Ismail ibn Mohammed ibn Abdallah ibn Harzihim/Hirzihim (also: Sidi Hrazem or Sidi Harazim) was born in Fes, Morocco and died in tha ...

),

Ibn al-Khatib

Lisan ad-Din Ibn al-Khatib ( ar, لسان الدين ابن الخطيب, Lisān ad-Dīn Ibn al-Khaṭīb) (Born 16 November 1313, Loja– died 1374, Fes; full name in ar, محمد بن عبد الله بن سعيد بن عبد الله بن � ...

, and

Al-Wazzan (

Leo Africanus

Joannes Leo Africanus (born al-Hasan Muhammad al-Wazzan, ar, الحسن محمد الوزان ; c. 1494 – c. 1554) was an Andalusian diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book '' Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later ...

) as well as the Jewish theologian

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

.

Sufi literature

Sufi literature consists of works in various languages that express and advocate the ideas of Sufism.

Sufism had an important influence on medieval literature, especially poetry, that was written in Arabic, Persian, Turkic and Urdu. Sufi doctr ...

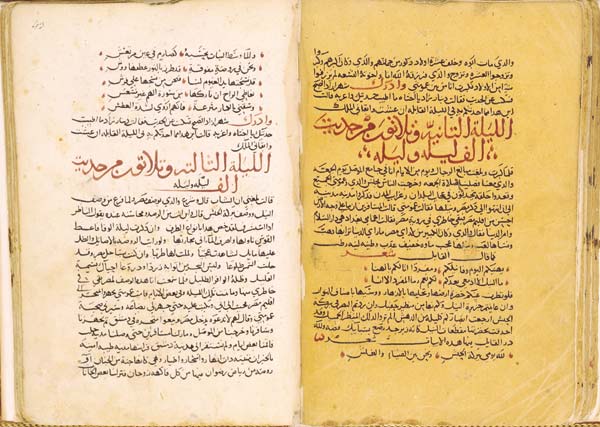

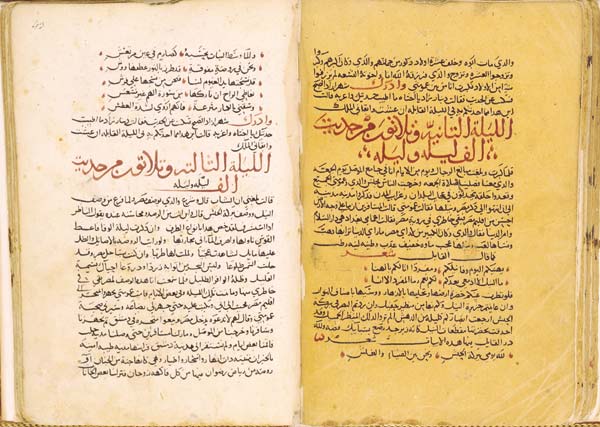

played an important role in literary and intellectual life in the region from this early period, such as

Muhammad al-Jazuli's book of prayers ''

Dala'il al-Khayrat

''Dalāil al-khayrāt wa-shawāriq al-anwār fī dhikr al-ṣalāt alá al-Nabī al-mukhtār'' ( ar, دلائل الخيرات وشوارق الأنوار في ذكر الصلاة على النبي المختار, translation=Waymarks of Benefit ...

''.

The

Zaydani Library

The Zaydani Library (Arabic: الخزانة الزيدانية, ''Al-Khizaana Az-Zaydaniya'') or the Zaydani Collection is a collection of manuscripts originally belonging to Sultan Zaydan Bin Ahmed that were taken by Spanish privateers in Atlanti ...

, the library of the

Saadi Sultan

Zidan Abu Maali

Zidan Abu Maali ( ar, زيدان أبو معالي) (? – September 1627; or Muley Zidan) was the embattled Saadi Sultan of Morocco from 1603 to 1627. He was the son and heir of Ahmad al-Mansur by his wife Lalla Aisha bint Abu Bakkar, a lady of ...

, was stolen by Spanish privateers in the 16th century and kept at the

El Escorial Monastery.

Mamluk

During the

Mamluk Sultanate

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 16th ...

,

Ibn Abd al-Zahir and

Ibn Kathir

Abū al-Fiḍā’ ‘Imād ad-Dīn Ismā‘īl ibn ‘Umar ibn Kathīr al-Qurashī al-Damishqī (Arabic: إسماعيل بن عمر بن كثير القرشي الدمشقي أبو الفداء عماد; – 1373), known as Ibn Kathīr (, was ...

were notable writers of history.

Ottoman

Significant poets of Arabic literature in the time of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

included ,

Al-Busiri

Al-Būṣīrī ( ar, ابو عبد الله محمد بن سعيد بن حماد الصنهاجي البوصيري, Abū ʿAbdallāh Muhammad ibn Saʿīd al-Ṣanhājī al-Būṣīrī; 1212–1294) was a Sanhaji Berber Muslim poet belong ...

author of "''

Al-Burda

''Qasīdat al-Burda'' ( ar, قصيدة البردة, "Ode of the Mantle"), or ''al-Burda'' for short, is a thirteenth-century ode of praise for the Islamic prophet Muhammad composed by the eminent Sufi mystic Imam al-Busiri of Egypt. The poe ...

''",

Ibn al-Wardi Abū Ḥafs Zayn al-Dīn ʻUmar ibn al-Muẓaffar Ibn al-Wardī ( ar, عمر ابن مظفر ابن الوردي), known as Ibn al-Wardi, was an Arab historian -, the author of ''Kharīdat al-ʿAjā'ib wa farīdat al-gha'rāib'' ("The Pearl of wond ...

,

Safi al-Din al-Hilli, and

Ibn Nubata.

Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi

Shaykh 'Abd al-Ghani ibn Isma′il al-Nabulsi (an-Nabalusi) (19 March 1641 – 5 March 1731), was an eminent Sunni Muslim scholar, poet, and author on works about Sufism, ethnography and agriculture.

Family origins

Abd al-Ghani's family descen ...

wrote on various topics including theology and travel.

Nahda

During the 19th century, a revival took place in Arabic literature, along with much of Arabic culture, and is referred to in Arabic as "''

al-Nahda

The Nahda ( ar, النهضة, translit=an-nahḍa, meaning "the Awakening"), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabic-speaking regions of the Ottoman Empire, notably in Egypt, ...

''", which means "the renaissance". There was a strand of

neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

in the Nahda, particularly among writers such as

Tahtawi,

Shidyaq,

Yaziji, and

Muwaylihi, who believed in the ''iḥyāʾ'' "reanimation" of Arabic literary heritage and tradition.

The translation of foreign literature was a major element of the Nahda period. An important translator of the 19th century was

Rifa'a al-Tahtawi

Rifa'a at-Tahtawi (also spelt Tahtawy; ar, رفاعة رافع الطهطاوي, ; 1801–1873) was an Egyptian writer, teacher, translator, Egyptologist and renaissance intellectual. Tahtawi was among the first Egyptian scholars to write about ...

, who founded the

School of Languages (also knowns as ''School of Translators'') in 1835 in Cairo. In the 20th century,

Jabra Ibrahim Jabra

Jabra Ibrahim Jabra (28 August 1919 – 12 December 1994) ( ar, جبرا ابراهيم جبرا) was a Iraqi-Palestinian author, artist and intellectual born in Adana in French-occupied Cilicia to a Syriac Orthodox Christian family. His famil ...

, a

Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

-

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

i intellectual living mostly in Bagdad, translated works by

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

,

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

,

Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish novelist, dramatist, short story writer, theatre director, poet, and literary translator. His literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal and tragicomic expe ...

or

William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi, where Faulkner spent most of ...

, among many others.

This resurgence of new writing in Arabic was confined mainly to cities in

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

,

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

until the 20th century, when it spread to other countries in the region. This cultural renaissance was not only felt within the Arab world, but also beyond, with a growing interest in

translating

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transl ...

of Arabic works into European languages. Although the use of the Arabic language was revived, particularly in poetry, many of the

tropes of the previous literature, which served to make it so ornate and complicated, were dropped.

Just as in the 8th century, when a movement to translate

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

and other literature had helped vitalise Arabic literature, another translation movement during this period would offer new ideas and material for Arabic literature. An early popular success was ''

The Count of Monte Cristo

''The Count of Monte Cristo'' (french: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel written by French author Alexandre Dumas (''père'') completed in 1844. It is one of the author's more popular works, along with ''The Three Musketeers''. Li ...

'', which spurred a host of

historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

s on similar Arabic subjects.

Jurji Zaydan

Jurji Zaydan ( ar, جرجي زيدان, ; December 14, 1861 – July 21, 1914) was a prolific Lebanese novelist, journalist, editor and teacher, most noted for his creation of the magazine ''Al-Hilal (magazine), Al-Hilal'', which he used to seri ...

and

Niqula Haddad

Niqula Haddad was a Syrian Socialist, and was brother in law to Farah Antun.

Early life

Niqula Haddad was born into an orthodox family in 1870.Reid, Donald M. “The Syrian Christians and Early Socialism in the Arab World.” ''International J ...

were important writers of this genre.

Poetry

During the

Nahda

The Nahda ( ar, النهضة, translit=an-nahḍa, meaning "the Awakening"), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabic-speaking regions of the Ottoman Empire, notably in Egypt, Leb ...

, poets like

Francis Marrash,

Ahmad Shawqi

Ahmed Shawqi (also written Chawki; ar, أحمد شوقي, , ; ; 1868–1932), nicknamed the Prince of Poets ( ar, أمير الشعراء ''Amīr al-Shu‘arā’''), was an Arabic poet laureate, to the Arabic literary tradition.

Life

Raised ...

and

Hafiz Ibrahim

Hafez Ibrahim ( ar, حافظ إبراهيم, ; 1871–1932) was a well known Egyptian poet of the early 20th century. He was dubbed the "Poet of the Nile", and sometimes the "Poet of the People", for his political commitment to the poor. His p ...

began to explore the possibility of developing the classical poetic forms. Some of these neoclassical poets were acquainted with Western literature but mostly continued to write in classical forms, while others, denouncing blind imitation of classical poetry and its recurring themes,

sought inspiration from French or English

romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

.

The next generation of poets, the so-called Romantic poets, began to absorb the impact of developments in Western poetry to a far greater extent, and felt constrained by

Neoclassical traditions which the previous generation had tried to uphold. The

Mahjar

The Mahjar ( ar, المهجر, translit=al-mahjar, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and Palestine ...

i poets were emigrants who mostly wrote in the Americas, but were similarly beginning to experiment further with the possibilities of Arabic poetry. This experimentation continued in the Middle East throughout the first half of the 20th century.

Prominent poets of the

Nahda

The Nahda ( ar, النهضة, translit=an-nahḍa, meaning "the Awakening"), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabic-speaking regions of the Ottoman Empire, notably in Egypt, Leb ...

, or "Renaissance," were

Nasif al-Yaziji

Nāṣīf bin ʻAbd Allāh bin Nāṣīf bin Janbulāṭ bin Saʻd al-Yāzijī (; March 25, 1800 – February 8, 1871) was a Lebanese author at the times of the Ottoman Empire and father of Ibrahim al-Yaziji. He was one of the leading figures in ...

;

Mahmoud Sami el-Baroudi

Mahmoud Sami Al Baroudi ( ar, محمود سامي البارودي; June 11, 1839 – December 11, 1904) was a significant Egyptian political figure and a prominent poet. He served as 5th Prime Minister of Egypt from 4 February 1882 until 26 May 1 ...

, , , and

Hafez Ibrahim

Hafez Ibrahim ( ar, حافظ إبراهيم, ; 1871–1932) was a well known Egyptian poet of the early 20th century. He was dubbed the "Poet of the Nile", and sometimes the "Poet of the People", for his political commitment to the poor. His p ...

;

Ahmed Shawqi

Ahmed Shawqi (also written Chawki; ar, أحمد شوقي, , ; ; 1868–1932), nicknamed the Prince of Poets ( ar, أمير الشعراء ''Amīr al-Shu‘arā’''), was an Arabic poet laureate, to the Arabic literary tradition.

Life

Raised ...

;

Jamil Sidqi al-Zahawi

Jamil Sidqi al-Zahawi ( ar, جميل صدقي الزهاوي, ; 17 June 1863 – January 1936) was a prominent Iraqi poet and philosopher. He is regarded as one of the greatest contemporary poets of the Arab world and was known for his defence of ...

,

Maruf al Rusafi

Ma'ruf bin Abdul Ghani al Rusafi (1875–1945) (Arabic: معروف الرصافي) was a poet, educationist and literary scholar from Iraq. He is considered by many as a controversial figure in modern Iraqi literature due to his advocacy of freed ...

, , and

Khalil Mutran

Khalil Mutran ( ar, خليل مطران, ; July 1, 1872 – June 1, 1949), also known by the sobriquet ''Shā‘ir al-Quṭrayn'' ( ar, شاعر القطرين, links=no / literally meaning "the poet of the two countries") was a Lebanese poet ...

.

Prose

Rifa'a at-Tahtawi

Rifa'a at-Tahtawi (also spelt Tahtawy; ar, رفاعة رافع الطهطاوي, ; 1801–1873) was an Egyptian writer, teacher, translator, Egyptologist and renaissance intellectual. Tahtawi was among the first Egyptian scholars to write about ...

, who lived in Paris from 1826 to 1831, wrote about his experiences and observations and published it in 1834.

Butrus al-Bustani

Butrus al-Bustani ( ar, بطرس البستاني, ; 1819–1883) was a writer and scholar from present day Lebanon. He was a major figure in the Nahda, which began in Egypt in the late 19th century and spread to the Middle East.

He is consi ...

founded the journal

''Al-Jinan'' in 1870 and started writing the first encyclopedia in Arabic:

Da'irat ul-Ma'arif in 1875.

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq

Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq ( ar, أحمد فارس الشدياق, ; born Faris ibn Yusuf al-Shidyaq; born 1805 or 1806; died 20 September 1887) was a scholar, writer and journalist who grew up in what is now present-day Lebanon. A Maronite Christia ...

published a number of influential books and was the editor-in-chief of in Tunis and founder of in

Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

.

Adib Ishaq

Adib Ishaq ( ar, اديب اسحق, ; 21 January 1856 – 12 June 1885) was an important Syrian literary figure of nineteenth-century Arab Nahda.

Born in Damascus (then a city of the Ottoman Empire, and the present-day capital of Syria), he was ...

spent his career in journalism and theater, working for the expansion of the press and the rights of the people.

and

Muhammad Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, infl ...

founded the revolutionary anti-colonial pan-Islamic journal ''

Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa

''Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa'' (, ) was an Islamic revolutionary journal founded by Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī. Despite only running from 13 March 1884 to October 1884, it was one of the first and most important publications of the ...

'',

Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi

'Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi ( ar, عبد الرحمن الكواكبي, -c.1902) was a Syrian author and Pan-Arab solidarity supporter. He was one of the most prominent intellectuals of his time; however, his thoughts and writings continue to be r ...

,

Qasim Amin

Qasim Amin (, arz, قاسم أمين; 1 December 1863, in AlexandriaPolitical and diplomatic history of the Arab world, 1900-1967, Menahem Mansoor – April 22, 1908 in Cairo) was an Egyptian jurist, Islamic Modernist and one of the founders ...

, and

Mustafa Kamil Mustafa Kamal, Mostafa Kamal or variations may refer to:

* Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938), Turkish field marshal, revolutionary statesman, and founder of the Republic of Turkey as well as its first President.

*Mustafa Kemal Kurdaş (1920–20 ...

were reformers who influenced public opinion with their writing.

Saad Zaghloul

Saad Zaghloul ( ar, سعد زغلول / ; also ''Sa'd Zaghloul Pasha ibn Ibrahim'') (July 1859 – 23 August 1927) was an Egyptian revolutionary and statesman. He was the leader of Egypt's nationalist Wafd Party.

He led a civil disobedience ...

was a revolutionary leader and a renowned orator appreciated for his eloquence and reason.

Ibrahim al-Yaziji

Ibrahim al-Yaziji (Arabic ابراهيم اليازجي, ''Ibrahim al-Yāzijī''; 1847–1906) was an Arab Christian philosopher, philologist, poet and journalist. He belonged to the Greek Catholic population of the Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebano ...

founded the newspaper ''

an-Najah'' ( "Achievement") in 1872, the magazine ''

At-Tabib'', the magazine

''Al-Bayan'', and the magazine ''

Ad-Diya

Between 1898 and 1906, the Arabic periodical ''aḍ-Ḍiyā''ʾ (Arabic: ''Illumination'') was published twice a month in Cairo. There are eight year's issues with 24 numbers each (first to third year), resp. 20 numbers each (fourth to eighth yea ...

'' and translated the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

into Arabic.

launched a newspaper called ''al-Istiqama'' (, " Righteousness") to challenge Ottoman authorities and push for social reforms, but they shut it down in the same year.

Mustafa Lutfi al-Manfaluti

Mustafa Lutfi el-Manfaluti ( ar, مصطفى لطفي المنفلوطي, ; 1876–1924) was an Egyptians, Egyptian writer and poet who wrote many famous Arabic books and was born in the Upper Egyptian city of Manfalut to an Egyptians, Egyptian fat ...

, who studied under Muhammad Abduh at

Al-Azhar University

, image = جامعة_الأزهر_بالقاهرة.jpg

, image_size = 250

, caption = Al-Azhar University portal

, motto =

, established =

*970/972 first foundat ...

, was a prolific essayist and published many articles encouraging the people to reawaken and liberate themselves.

Suleyman al-Boustani

Suleyman al-Boustani (Arabic: سليمان البـسـتاني / ALA-LC: ''Sulaymān al-Bustānī'', tr, Süleyman el-Büstani; 1856–1925) was born in Bkheshtin, Lebanon.

He was a statesman, teacher, poet and historian.

He was a Maronite Ca ...

translated the ''

Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'' into Arabic and commented on it.

Khalil Gibran

Gibran Khalil Gibran ( ar, جُبْرَان خَلِيل جُبْرَان, , , or , ; January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931), usually referred to in English as Kahlil Gibran (pronounced ), was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and visual artist ...

and

Ameen Rihani

Ameen Rihani (Amīn Fāris Anṭūn ar-Rīḥānī) ( ar, أمين الريحاني / ALA-LC: ''Amīn ar-Rīḥānī''; Freike, Lebanon, November 24, 1876 – September 13, 1940), was a Lebanese American writer, intellectual and political a ...

were two major figures of the

Mahjar

The Mahjar ( ar, المهجر, translit=al-mahjar, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and Palestine ...

movement within the Nahda.

Jurji Zaydan

Jurji Zaydan ( ar, جرجي زيدان, ; December 14, 1861 – July 21, 1914) was a prolific Lebanese novelist, journalist, editor and teacher, most noted for his creation of the magazine ''Al-Hilal (magazine), Al-Hilal'', which he used to seri ...

founded

''Al-Hilal'' magazine in 1892, founded

''Al-Muqtataf'' in 1876,

Louis Cheikho

Louis Cheikho, ar, لويس شيخو, born Rizqallâh Cheikho (1859–1927) was a Jesuit Chaldean Catholic priest, Orientalist and Theologian. He pioneered Eastern Christian and Assyrian Chaldean literary research and made major contributio ...

founded the journal ''

Al-Machriq

''Al-Machriq'' (Arabic: ''The East'') was a journal founded in 1898 by Jesuit and Chaldean priest Louis Cheikhô, published by Jesuit fathers of Saint Joseph University in Beirut, Lebanon. The subtitle was ''Revue Catholique Orientale. Scienc ...

'' in 1898.

Other notable figures of the Nahda were

Mostafa Saadeq Al-Rafe'ie

Mostafa Saadeq Al-Rafe'ie

Mostafa Saadeq Al-Rafe' (1 January 1880 – May 1937) was an Egyptian poet, born in Egypt in Qalyubiyya, Egypt.

Early life

His maternal grandfather was Sheikh Eltoukhy (originally from Toukh, a famous Egyptian city) ...

and

May Ziadeh

May Elias Ziadeh ( ; ar, مي إلياس زيادة, ; 11 February 1886 – 17 October 1941) was a Lebanese people, Lebanese-Palestinians, Palestinian poet, essayist, and translator, who wrote many different works both in Arabic language, Ar ...

.

Muhammad al-Kattani

Muhammad Bin Abdul-Kabir Al-Kattani (محمد بن عبد الكبير الكتاني; from 1873 - May 4, 1909), also known by his ''kunya'' Abu l-Fayḍ () or simply as Muhammad Al-Kattani, was a Moroccan Sufi ''faqih'' (scholar of Islamic la ...

, founder of one of the first arabophone newspapers in Morocco, called ''

At-Tā'ūn'', and author of several poetry collections, was a leader of the Nahda in the Maghreb.

Modern literature

Beginning in the late 19th century, the Arabic novel became one of the most important forms of expression in Arabic literature. The rise of an ''efendiyya'', an elite, secularist urban class with a Western education, gave way to new forms of literary expression: modern Arabic fiction.

This new

bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

class of ''literati'' used

theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actor, actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The p ...

from the 1850s, starting in Lebanon, and the

private press

Private press publishing, with respect to books, is an endeavor performed by craft-based expert or aspiring artisans, either amateur or professional, who, among other things, print and build books, typically by hand, with emphasis on design, gra ...

from the 1860s and 1870s to spread its ideas, challenge traditionalists, and establish its position in a rapidly transforming society.

The modern Arabic novel, particularly as a means of social critique and reform, has its roots in a deliberate departure from the traditionalist language and aesthetics of classical ''adab'' for "less embellished but more entertaining narratives."

This direction began with translations from French and English, followed by social romances by and other writers—particularly Christians.

narrative ''

Way, Idhan Lastu bi-Ifranjī!'' (1859-1860) was an early example.

The emotionalism of early 20th century writers such as

Mustafa Lutfi al-Manfaluti

Mustafa Lutfi el-Manfaluti ( ar, مصطفى لطفي المنفلوطي, ; 1876–1924) was an Egyptians, Egyptian writer and poet who wrote many famous Arabic books and was born in the Upper Egyptian city of Manfalut to an Egyptians, Egyptian fat ...

and

Kahlil Gibran

Gibran Khalil Gibran ( ar, جُبْرَان خَلِيل جُبْرَان, , , or , ; January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931), usually referred to in English as Kahlil Gibran (pronounced ), was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and visual artist ...

, who wrote with heavy

moralism

Moralism is any philosophy with the central focus of applying moral judgements. The term is commonly used as a pejorative to mean "being overly concerned with making moral judgments or being illiberal in the judgments one makes".

Moralism has s ...

and

sentimentality

Sentimentality originally indicated the reliance on feelings as a guide to truth, but in current usage the term commonly connotes a reliance on shallow, uncomplicated emotions at the expense of reason.

Sentimentalism in philosophy is a view in ...

, equated the novel as a literary form with imported Western ideas and "shallow sentimentalism."

Writers such as of

Al-Madrasa al-Ḥadītha

''Al-Madrasa al-Ḥadītha'' ( or 'The New School') was a modernist movement in Arabic literature that began in 1917 in Egypt. The movement is associated with the development of the short story in the earlier periods of modern Arabic literature. D ...

"the Modern School," calling for an ''adab qawmī "''national literature," largely avoided the novel and experimented with short stories instead.

1913 novel

''Zaynab'' was a compromise, as it included heavy sentimentality but portrayed local personality and characters.

Throughout the 20th century, Arabic writers in poetry, prose and theatre plays have reflected the changing political and social climate of the Arab world.

Anti-colonial

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

themes were prominent early in the 20th century, with writers continuing to explore the region's relationship with the West. Internal political upheaval has also been a challenge, with writers suffering censorship or persecution.

The

interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

featured writers such as

Taha Hussein

Taha Hussein (, ar, طه حسين; November 15, 1889 – October 28, 1973) was one of the most influential 20th-century Egyptian writers and intellectuals, and a figurehead for the Nahda, Egyptian Renaissance and the modernism, modernist movem ...

, author of ''

Al-Ayyām,''

Ibrahim al-Mazini

Ibrahim Abd al-Qadir al-Mazini ( ar, إبراهيم عبد القادر المازني, ; born August 19, 1889 or 1890; died July 12 or August 10, 1949) was an Egyptian poet, novelist, journalist, and translator.

Early life

Al-Mazini was born in ...

,

Abbas Mahmoud al-Aqqad

Abbas Mahmoud al-Aqqad ( ar, عباس محمود العقاد, ; 28 June 1889 – 12 March 1964) was an Egyptians, Egyptian journalist, poet and literary critic, , and

Tawfiq al-Hakim

Tawfiq al-Hakim or Tawfik el-Hakim ( arz, توفيق الحكيم, ; October 9, 1898 – July 26, 1987) was a prominent Egyptian writer and visionary. He is one of the pioneers of the Arabic novel and drama. The triumphs and failures that ar ...

.

The acceptance of suffering in al-Hakim's 1934 , is exemplary of the disappointment that prevailed over the idealism of the new middle class.

As a result of increasing

industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and

urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly t ...

, binary struggles such as the "materialism of the West" against the "spiritualism of the East," "progressive individuals and a backward, ignorant society," and "a city-versus-countryside divide" were common themes in the literature of this period and since.

There are many contemporary Arabic writers, such as

Mahmoud Saeed

Mahmoud Saeed (born 1939) is an Iraqi-born American novelist.

Born in Mosul, Saeed has written more than twenty novels and short story collections, and hundreds of articles. He started writing short stories at an early age. He wrote an award-w ...

(Iraq) who wrote ''Bin Barka Ally'', and ''I Am The One Who Saw (Saddam City)''. Other contemporary writers include

Sonallah Ibrahim

Son'allah Ibrahim ( ar, صنع الله إبراهيم ''Ṣunʻ Allāh Ibrāhīm'') (born 1937) is an Egyptian novelist and short story writer and one of the " Sixties Generation" who is known for his leftist and nationalist views which are expr ...

and

Abdul Rahman Munif

Abdelrahman bin Ibrahim al-Munif ( ar, عَبْدُ الرَّحْمٰن المُنِيفٌ) known by his nickname Abdelrahman Munif (May 29, 1933 – January 24, 2004) was a Saudi Arabian novelist, short story writer, memoirist, journalist ...

, who were imprisoned by the government for their critical opinions. At the same time, others who had written works supporting or praising governments, were promoted to positions of authority within cultural bodies.

Nonfiction

Nonfiction, or non-fiction, is any document or media content that attempts, in good faith, to provide information (and sometimes opinions) grounded only in facts and real life, rather than in imagination. Nonfiction is often associated with be ...

writers and academics have also produced political polemics and criticisms aiming to re-shape Arabic politics. Some of the best known are

Taha Hussein

Taha Hussein (, ar, طه حسين; November 15, 1889 – October 28, 1973) was one of the most influential 20th-century Egyptian writers and intellectuals, and a figurehead for the Nahda, Egyptian Renaissance and the modernism, modernist movem ...

's ''

The Future of Culture in Egypt

''The Future of Culture in Egypt'' ( ar, مستقبل الثقافه في مصر ) is a 1938 book by the Egyptian writer Taha Hussein.

The book is a work of Egyptian nationalism advocating both independence and the adoption of various European ...

'', which was an important work of

Egyptian nationalism

Egyptian nationalism is based on Egyptians and Egyptian culture. Egyptian nationalism has typically been a civic nationalism that has emphasized the unity of Egyptians regardless of their ethnicity or religion. Egyptian nationalism first manifes ...

, and the works of

Nawal el-Saadawi

Nawal El Saadawi ( ar, نوال السعداوي, , 22 October 1931 – 21 March 2021) was an Egyptian feminist writer, activist and physician. She wrote many books on the subject of women in Islam, paying particular attention to the practice ...

, who campaigned for

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

. Tayeb Salih from

Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

and Ghassan Kanafani from Palestine are two other writers who explored identity in relationship to foreign and domestic powers, the former writing about colonial/post-colonial relationships, and the latter on the repercussions of the Palestinian struggle.

Poetry

After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, there was a largely unsuccessful movement by several poets to write poems in

free verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry, which in its modern form arose through the French ''vers libre'' form. It does not use consistent meter patterns, rhyme, or any musical pattern. It thus tends to follow the rhythm of natural speech.

Definit ...

(''shi'r hurr''). Iraqi poets

Badr Shakir al-Sayyab

Badr Shakir al Sayyab ( ar, بدر شاكر السياب) (December 24, 1926 in Jaykur, near Basra – December 24, 1964 in Kuwait) was a leading Iraqi poet, well known throughout the Arab world and one of the most influential Arab poets of all ti ...

and

Nazik Al-Malaika

Nazik al-Malaika ( ar, نازك الملائكة; 23 August 1923 – 20 June 2007) was an Iraqi poet. Al-Malaika is noted for being among the first Arabic poets to use free verse.

Early life and career

Al-Malaika was born in Baghdad to a cult ...

(1923-2007) are considered to be the originators of free verse in Arabic poetry. Most of these experiments were abandoned in favour of

prose poetry

Prose poetry is poetry written in prose form instead of verse form, while preserving poetic qualities such as heightened imagery, parataxis, and emotional effects.

Characteristics

Prose poetry is written as prose, without the line breaks associ ...

, of which the first examples in modern Arabic literature are to be found in the writings of

Francis Marrash, and of which two of the most influential proponents were Nazik al-Malaika and

Iman Mersal. The development of

modernist poetry

Modernist poetry refers to poetry written between 1890 and 1950 in the tradition of modernist literature, but the dates of the term depend upon a number of factors, including the nation of origin, the particular school in question, and the biases ...

also influenced poetry in Arabic. More recently, poets such as

Adunis

Ali Ahmad Said Esber (, North Levantine: ; born 1 January 1930), also known by the pen name Adonis or Adunis ( ar, أدونيس ), is a Syrian people, Syrian poet, essayist and translator. He led a modernist revolution in the second half of the ...

have pushed the boundaries of stylistic experimentation even further.

Poetry retains a very important status in the Arab world.

Mahmoud Darwish

Mahmoud Darwish ( ar, محمود درويش, Maḥmūd Darwīsh, 13 March 1941 – 9 August 2008) was a Palestinian poet and author who was regarded as the Palestinian national poet. He won numerous awards for his works. Darwish used Palestine ...

was regarded as the Palestinian national poet, and his funeral was attended by thousands of mourners. Syrian poet

Nizar Qabbani

Nizar Tawfiq Qabbani ( ar, نزار توفيق قباني, , french: Nizar Kabbani; 21 March 1923 – 30 April 1998) was a Syrian diplomat, poet, writer and publisher. He is considered to be Syria's National Poet. His poetic style combines sim ...

addressed less political themes, but was regarded as a cultural icon, and his poems provide the lyrics for many popular songs.

Novels

Two distinct trends can be found in the ''nahda'' period of revival. The first was a neo-classical movement which sought to rediscover the literary traditions of the past, and was influenced by traditional literary genres—such as the ''

maqama

''Maqāmah'' (مقامة, pl. ''maqāmāt'', مقامات, literally "assemblies") are an (originally) Arabic prosimetric literary genre which alternates the Arabic rhymed prose known as '' Saj‘'' with intervals of poetry in which rhetorical ...

''—and works like ''

One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

''. In contrast, a modernist movement began by translating Western modernist works—primarily novels—into Arabic.

In the 19th century, individual authors in

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

,

Lebanon